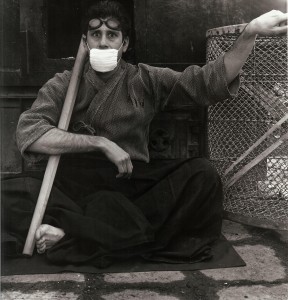

Photo by Ryutaro Hidaka (1990)

Besides being a musician, Sohrab is also a certified teacher of Kendo, the modern Japanese martial art of sword-fighting. Studying Kendo was the main reason for him to leave his hometown Hamburg (Germany) in 1974. He was twenty years old and ready to challenge himself in Japan which was almost unknown to Europeans.

In December of 1974, Sohrab was welcomed by his Kendo teacher Yasushi Okumura Sensei in Osaka who had taught him Kendo at the Alster Dojo in Hamburg in 1974. He was an allergy researcher at the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine (Bernhard-Nocht-Institut für Tropenmedizin). Sohrab “fell in love” with his teacher and adored him. No wonder he got motivated to go to Osaka the next year after his high school graduation in the fall of 1973 continuing his apprenticeship there.

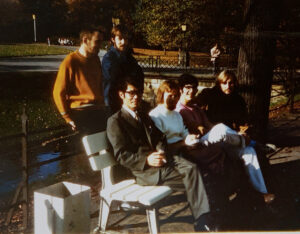

Another person who was very influential on Sohrab and became kind of a mentor was Feliks Hoff. Feliks was 8 years older than Sohrab. Working as a social worker and trainer at that time. He was also teaching Judo and running Yoga classes at Alster Dojo. He was very educated and had a lot of knowledge about anything related to Japan, such as Zen Buddhism, Martial Arts, Food, literature, Haiku, and Japanese Classical music (in fact, he played the cello and worked on his shakuhachi chops as well); and politics. Before leaving Hamburg he invited Sohrab for a Sushi dinner at his home.

About Feliks Hoff

He has been training for over 51 years, during this time he achieved the rank of Kyoshi 6-Dan from the All Japan Kyudo Federation and was instrumental in spreading budo, specifically Kyudo in Germany and Europe. Hoff Sensei led the founding of the first kyudo group in Germany in 1969, the European Kyudo Federation in 1980, and the German Kyudo Federation in 1994, was the competition coordinator for the European Kyudo Federation for 28 years, and a member of the founding committee of the International Kyudo Federation, sitting as a director for the first 10 years of existence. Hoff is also the author of one of the preeminent books on Kyudo internationally, called Kyudo: The Way of the Bow

For a couple of weeks, he stayed at his teacher’s. His family was very friendly with him, especially his wife who could speak English – introducing him to Japanese everyday life by starting how to hold the chopsticks. While staying with his family, Okumura decided to find the right Japanese name for Sohrab Saadat Ladjevardi. His original name was too hard for Japanese to remember. So he came up with Sadato (last name) Sohi (first name), a variant of the original name.

Because Okumura was very busy teaching medicine at universities and working as a primary doctor at medical clinics, he had no time to teach Sohrab Kendo. So, he referred Sohrab to Ota Sensei the Kendo chief instructor at the Osaka Municipal Martial Arts Center Shudokan, a training hall in the Osaka Castle.

Besides Kendo, Sohrab also studied and practiced Iaido and Judo, but gave both up two years later when he felt he should focus only on Kendo.

So every day from morning till evening Sohrab studied and practiced Kendo. He became so popular among Osaka’s Kendo teachers that he was invited to their dojos. They taught him the secrets of their styles. At that time he was the only foreigner practicing at the head dojo of the Osaka Police.

During his third year, he found his real master Masao Sakudo Sensei (1976 – 1982) who was teaching at the Osaka College of Physical Education (later Osaka University of Health and Sport Sciences).

Sohrab decided to enter his school and stayed there for the next six years studying under him. When he graduated in 1982, he was the holder of the 5th dan and was a certified teacher. Besides Sakudo Sensei (Kyoshi 7 Dan), other important teachers took care of Sadato, such as Masanori Yuno Sensei, Saburo Abe (Hanshi 8 Dan, Tokyo Police), Ota Sensei (Kyoshi 7 Dan, Shudokan), Yuji Ikeda Sensei (Hanshi 8 Dan), Yoshinobu Nishi Sensei (Hanshi 8 Dan, Shudokan), Masao Komorizono Sensei (Hanshi 8 Dan, Shudokan), Mitsuo Arima Sensei (Kyoshi 7 Dan, Osaka Police), Kuniyoshi Okuzono (Hanshi 8 Dan, Osaka Police) and Takahashi Sensei (Kyoshi 7 Dan, Kyoto Police).

In 1984 he moved to Tokyo and became a student of Hironobu Sato Sensei (1984–2008) who was teaching at the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Dojo and the Higashi Nakano Shudokan.

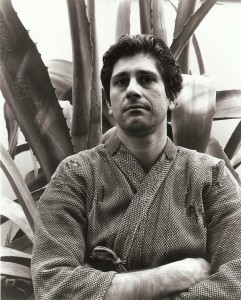

Speaking of his Kendo career: during his thirty-four years in Japan, he became a master in Kendo, and the first non-Japanese to pass all 6 Dan exams in Japan. He studied under two well-known Kendo masters: Masao Sakudo Sensei (1976 – 1982) in Osaka and Hironobu Sato Sensei (1984–2008) in Tokyo. After reaching a higher level through years of study of Kendo, he began to think about applying his philosophy and hard work to music.

In 1984 he left Osaka for Tokyo because he felt to improve his Kendo he needed to move to Tokyo. In Tokyo, the head Kendo teacher of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police, Hironobu Sato Sensei became his new teacher and last master. Under his guidance, Sohrab accomplished his studies and became a real Kendo master. In 1987 he passed the 6th dan examination and became the first foreigner to receive all his 6 dans in Japan and in the most speedy way:

Kendo1st dan and Judo 1st dan in 1974

Kendo 2nd dan in 1975

Kendo 3rd dan in 1976

Kendo 4th dan in 1978

Kendo 5th dan in 1981

Kendo 6th dan in 1987

All this said, how could Sohrab get involved with music when Kendo was the main thing in his life in Japan?

After 4 years of hard training, Sohrab felt that he needed something “extra” in his daily life. Studying Kendo wasn’t enough to enjoy and experience life. He felt that he was losing touch with the people around him. He had no time to do other things, such as going to see movies, go to concerts, socialize with people, have a girlfriend. When he was 24 years old he happened to go to a free Jazz concert. He enjoyed their “crazy” music. While listening he even found some similarities in their music with Kendo. After their show, Sohrab had a chance to talk to them and surprised them with the statement in broken Japanese: “Free Jazz is Kendo and Kendo is Free Jazz!” The band enjoyed the conversation with him so much that they invited him to their next rehearsal.

Sohrab was so happy after the concert to find out that Kendo was appliable to other things in common life, such as music. He realized that music would open a new door to the world. Kendo was only good for Japan, but music was something that could speak to anybody around the world.

After the first rehearsal, Sohrab asked the band to accept him as a member. They agreed and let him do vocals for a couple of months. Then they realized that his voice wasn’t “loud” enough, so they gave him a used alto sax to play on without teaching him how to play it. He just felt cool “blowing” his horn and fell in love with every new sound he got out of it. The horn player taught him the basic fingering of the keys and how to put the reed on the mouthpiece. That’s all! The rest he taught himself was based on Kendo. You could call him a “Kendo sax player playing Kendo music”. Sohrab never copied any other musician from the beginning and he has never been a sideman of any band. Without Kendo, Sohrab would never have become the musician he is now!

What did he learn from Kendo and how did he apply it to music?

To believe in himself and be original. Developing his style and getting an original sound.

To be able to listen to others and respond to them.

Kendo practice and real life are one.

When you learn something completely, you can apply it to other things, such as art, work, etc.